Promise or Tokenism? Assessing the EU’s Pay Transparency Directive in bridging the gender pay gap

Introduction

According to recent EuroStat research, the median wage gap in the European Union has remained persistent at 14.1 per cent. Moreover, the situation edges towards precarity due to the pandemic that has exposed a stark contrast between the union’s values, enshrined in egalitarianism and equality, and the practical reality of work and pay between the genders.

The EU’s Euro Monitor defines the gender pay gap as the difference in average gross hourly earnings between women and men, depending upon direct earnings before deductions such as income tax and social security contributions etc. In March 2021, the commission published a directive for the enforcement of transparency in pay as a means to strengthen the principle of equal pay for equal work. The proposal argues that over the years, women have matched up their professional skills, labour market and educational standards with men, and it is about time the gaps in wages were bridged as well. Hailing the move, Kira Marie Peter-Hansen, an MEP and member of the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance who sits on the Employment and Social Affairs Committee said, “With this directive, we are taking an important step towards gender equality, and shining a light on the problem of unequal pay.“

The directive proposes enforceable actions for employers on transparency in structures of pay and processes, along with the employees’ rights to information. However, contrarians argue that the impact of this directive will fall short of its promise, upon the directive’s own admission that limiting transparency has certain legislative and economic consequences for the policy. This article would thus examine the directive for its key takeaways, its impact, and challenges in its implementation. This is in an effort to understand if the directive has the strength to combat the pay gap, or if it’s a proposal that lacks adequate checks and balances; risking turning into a mere token to the principle of equality.

The Landscape: Governance and Key Takeaways

Some of the founding principles of the European Union are equality, promoting social and economic cohesion, and combating social exclusion — as enshrined in the Treaty of Rome of 1957, Article 157 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and in the directive 2006/54/EC1 (the ‘Recast Directive’). Yet, despite these legal frameworks, a labour market status quo remains whereby women earn less than men.

EU Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen stated, “We should not be shy about being proud of where we are or ambitious about where we want to go.” According to the European Centre of Social Welfare Policy and Research, an accumulated gap between employment and pay for both genders over a lifetime has an impact on pension funds, putting women at a higher risk of poverty than men. The report also highlights that it is not just the entry-level or mid-career level women who are marred by this disparity; it is also a highly prevalent phenomenon at the senior managerial levels — where the EU’s largest private sector companies include just 7.7 per cent of women as board members. Additionally, the EU’s parliament has just 32.2 percent of women making up the members of the parliament.

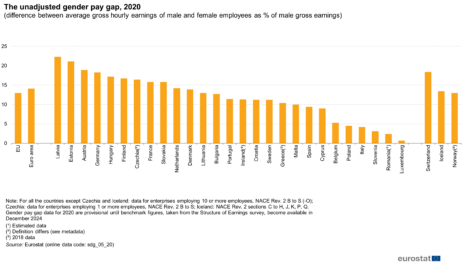

The figure on top of the page shows the overall (unadjusted) gap in wages at the EU member states level, usually based on single components. The unadjusted gender pay gap, according to the commission’s report, is the difference between the average gross hourly earnings of men and women but expressed as a percentage of male earnings. It does not take into account education, age, hours worked, or type of job.

According to the above figure, the gender pay gap varies by 21.6 percentage points, ranging from 0.7 percent in Luxembourg to 22.3 percent in Latvia. However, a narrower gender pay gap doesn’t mean more gender equality; some of the stated causes of wage disparity are for example: lower female employment, more female concentration in low-paid sectors or part-time work, an increase in the gender pay gap with age, etc.

Thus, in March 2021, the European Union confronted this pay inequity by addressing market inequalities, such as bringing institutions under the parasol of “work of equal value.” The key takeaways from the directive include:

- Mandatory Pay Range Advertising: employers will have to provide the level of pay or range of pay in job advertisements before conducting interviews.

- Pay Confidentiality: employers are not permitted to inquire about past pay history.

- Right to Information on Pay Levels: applicants can enquire about average pay ranges broken down by similar job profiles and gender by the potential employers.

- Public pay disclosure: if organisations have a staff count of 250 or more, it is mandatory to make pay gaps public. Additionally, if a gap of 5 percent or more exists, then a mandatory pay assessment is required with the existing workers’ representative/s and the national labour authorities.

- Compensatory Benefit: employees subjected to discrimination are eligible to file for compensation or arrears. The burden of proof lies with the employer.

- Legislative Empowerment: employee representatives and/or labour institutions are allowed to pursue legal or administrative actions for claims on behalf of employees.

- Penalties are states prerogative: EU member states can establish their own statutes on penalties and fines over violations of equal pay.

The Glass Ceiling

Despite the directive’s noble intent, critics urge a focus upon various shortcomings on the basis of the commission’s own Equal Pay directive impact assessment report, published in 2021. They highlight that the report risks the exclusion of two-thirds of European workers from pay transparency measures. It is worth noting the following unaddressed issues, such as:

- A lack of a definition of ‘work of equal values’ : Under the current state of the EU labour laws, ‘work of equal value’ is left undefined and is being applied to variable factors such as different occupations and personalities; characteristics of male and female employees (for example, working atypical hours, ethnicity, childcare etc.), in the same organisation.

- The pay reporting ceiling: mandatory gender pay reporting is limited to organisations with 250 or more employees, implying a difference in financial equality measurement, based on the nature of the organisation and differential pay based on the nature of employment (e.g., contractual, part-time, third-party, volunteer, etc.). Moreover, member states with a greater number of small enterprises (e.g., Greece, Cyprus, Italy) can have higher unreported pay discrimination and breaches in the directive’s compliance.

- Preferential Undercutting: The directive undermines its own mandates by undercutting the benchmark of 250 employees to 100 or 150 employees for some member states, such as Austria and Italy, arguing that the benefits of binding pay-transparency outweigh the costs of application. As a result, the actual impact of its own directive is reduced, and nearly 67% of workers across the EU are at risk of being excluded from the equal pay policy.

- Lack of awareness: Article 17 (1) of the directive proposes employees’ right to information, where employers shall be obligated to inform applicants about initial pay levels broken down by gender and job categories, the criteria used to determine pay levels and the scope of career progress offered. However, research shows that compared to men, women tend to face more “social penalty” or backlash for raising questions or engaging in negotiations” (Bowles, 2014[24]).

Furthermore, because the burden of the obligation to share information falls on the employer, the lack of awareness on employee rights, access to justice, and enforcement of legal frameworks in case of breach are significantly difficult for female applicants to access. This will lead to the watering down of the directive’s noble intentions.

Conclusion: Pandemic and the Voids

While the pandemic has severely impacted minimum wage workers due to the lack of temporary subsidies in Europe, women have borne the maximum brunt of the disproportionate impact (European Commission 2021). Though the directive for pay transparency has positively paved the way for renewed commitments, discussions and deliberations on the need for more gender pay parity. Yet, the scope of the directive also has a vast array of groundwork to curb formidable barriers such as gaps in the knowledge of existing inequalities, inadequate data, access to influence firm wage dispersions, opacity in the cost of policy application, and pay arrangements inside organisations – all of which are imperative for successfully bridging the GPG.

Despite many EU member states already having enforced the pay transparency measures, there remain several concerns resulting in non-committance, such as the right to freedom of business; breach of privacy laws; and the impact of slower average wage gains for males on the overall average profitability, thus creating a lose-lose for the cause of GPG (Bennedsen et al, 2019).

Finally, it is important to note that while the directive is extremely beneficial yet, without thorough gender-responsive measures for the labour market and industry sectors, building a healthier impact on the economy and achieving lower wage dispersions that bridge the gender pay gap will have a severe impact on the overall effectiveness of the policy, rendering it a mere tokenism towards the EU’s mission of equality for all.