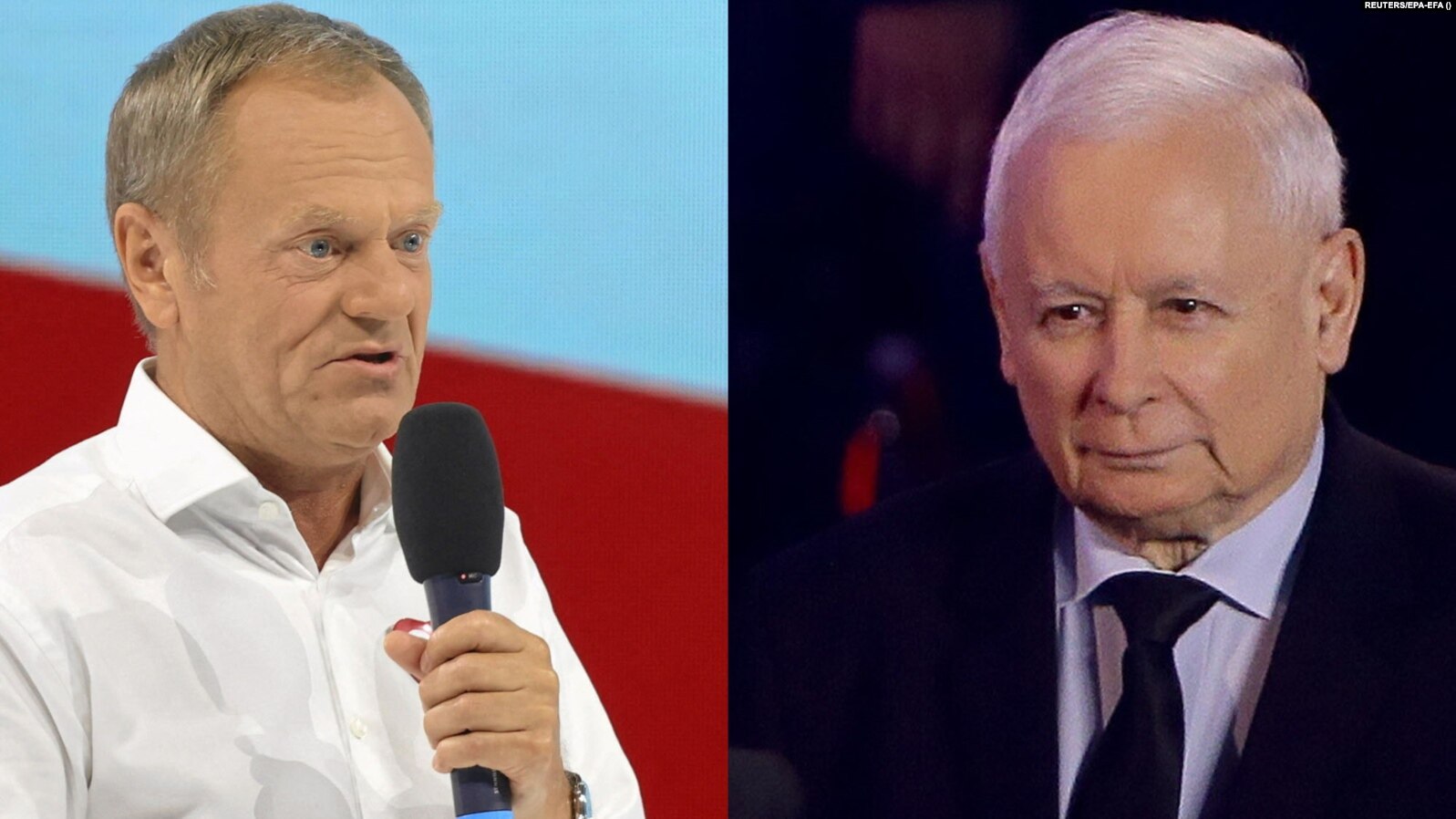

The 2023 Polish parliamentary election (held on 15 October 2023) has been widely expected to bring serious changes to Poland, and some to European politics as well, many hoping to see the fall of the right-winged governing party Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość – PiS) out of power after a long time and Poland taking a new, more pro-European track under the leadership of Donald Tusk, previous Polish Prime Minister, President of the European Council and of the European People’s Party.

During these elections, Polish people were to fill up seats in both the Sejm and the Senate, the first one being relevant to a potential new government. (Additionally, a referendum of four questions concerning economic and immigration policy of the government was held, but it has no real relevance to the governmental changes, it was more of a propaganda-tool by the government). The real question was if the “United Right” coalition (made by PiS and its allies) can hold its Sejm majority, giving the possibility to Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki to form a second government against the opposition (a coalition of the parties Civic Coalition, Third Way, and The Left), lead by Donald Tusk.

The results of the elections

As a result, the United Right won the most seats in the Sejm, but still fell short of a majority. The members of the opposition coalition have achieved a combined vote total of 54% in the Sejm, thus gaining the possibility to form a coalition government. (They have even won the majority in the Senate.) Voter turnout was 74.4%, the highest since the fall of communism, beating the previous records set in 1989 and 2019. Turnout among young voters was 74.7% among women and 73.1% among men, leading to some analysts talking about a “youthquake”, giving young voters a disproportionate impact on the outcome of the elections. Turnout for ages 18–29 reached 68.8% in this election, which is a whopping jump from the 46.4% of the previous elections in 2019; and among them, support for the governing parties has also fallen to 14.9% from 26.3% four years earlier which is one of the direct reasons of the election loss of Polish government parties.

How to create a new Polish government?

The process is regulated by Articles 154-155 of the Constitution of the Polish Republic and it follows the general pattern of parliamentary republics (even if some may argue that Poland is more of a semi-presidential republic, it is not).

According to Article 154, the President of the Republic (being Duda now) is responsible for nominating a Prime Minister (who shall be responsible to compile the “Council of Ministers”, meaning the governing body). The President has 14 days for that, counting from the time of the first sitting of the Sejm, in case of the ordinary elections (in the case of a premature resignation of the government, different rules apply, but those are not relevant here). The President has to appoint a Prime Minister together with other members of the Council of Ministers who are obliged to take oaths of office. So far the President is free to make his decision about the Prime Minister, but the Sejm still has to confirm him/her, and this is where troubles may start.

The Polish constitution dictates that the appointed Prime Minister shall (within 14 days after his/her appointment by the President) submit a governmental programme of his/her government to the Sejm, together with a motion requiring a vote of confidence, which has to be accepted by the Sejm with an absolute majority of votes in the presence of at least half of the statutory number of its members. This means that the Prime Minister practically has to be elected by the Sejm as well – a typical constitutional element of parliamentary republics as I have mentioned earlier. The final power of appointment of the Prime Minister is not in the hands of the President but of the Sejm.

If the process described above is not successful in any way – either in the case of the President not appointing a government or the appointed government fails due to the vote in the Sejm – the President gets out of the picture. In this case the Sejm gets 14 days to choose a Prime Minister (and members of the Council of Ministers, based on the proposal of that individual) of its own will, and vote about the appointment by an absolute majority of votes in the presence of at least half of the statutory number of Deputies. If this is done, the President of the Republic is under the obligation to appoint the rest of the members of the Council of Ministers and accept their oaths of office.

If the Sejm is not able to do so, under Article 155 of the Polish constitution the President may try appointing one more candidate for Prime Minister and if unsuccessful, he has to dissolve the Sejm (formally shortening its term of office) and order new elections to be held.

Putting it all together, the President of Poland is not such a powerful player as many argue – and President Duda cannot block the appointment of Donald Tusk. Even if he is going to appoint someone from PiS, clear oppositional majority in the Sejm will block his entry into office and in the next round, it is up to the Sejm to nominate someone, so the will of the opposition coalition will prevail, regardless of the will of President Duda. This is something that he will clearly understand and will not risk a political embarrassment with appointing someone who will clearly lose at the end of the process – making him a loser as well.

For those who are interested: these kinds of situations are not novel in parliamentary systems. A very similar one appeared in Hungary in 2002, when Viktor Orbán lost in the elections. While his party gained the most seats in the Hungarian parliament, the coalition of socialists and liberals gained an overall majority. There were serious concerns among the ranks of the opposition about the Hungarian President of the Republic at that time, the pro-Orbán Ferenc Mádl, possibly appointing Viktor Orbán, arguing very similarly to Duda right now. But it has never happened as he has clearly understood that it would not make any sense, and finally appointed the candidate of the oppositional parties, Péter Medgyessy. Parliamentary constitutional systems give power to presidents against the will of parliaments only in a temporary manner.

Concluding: we are sure to see a new government led by Donald Tusk in Poland.

Implications on the European Union

What changes could a Tusk-lead government bring to the relationship between Poland and the European Union and what effects would that government have on the European Union? EU relations have served as an important subject of debate and criticism during the past years in domestic politics, as the country has developed controversial policies (abortion, gay rights), built close relationship with other member states with similar problems (e.g. Hungary, more specifically with the government of Viktor Orbán), introduced changes in the judicial system, leading to an Article 7 proceeding and numerous infringement proceedings initiated by the European Commission and to the freezing of various Union funds (ca. 35 billion euros from the Recovery Fund and ca. 76 billion euros from the cohesion funds). It is safe to say that never before has this relationship been so tense, and obviously this has also had a bad effect on the popularity of the government, giving an advantage to the opposition – but now it means an incredible task.

No wonder that Donald Tusk has already had meetings with various EU leaders in Brussels, making access to these funds a top priority. But at the same time the various EU institutions are not going to rush for his help, trying to avoid the image of favouring anybody in the domestic political contest of Poland, even if Tusk has some serious advantage here, given his enormous experience.

Concerning the European Commission, we do not expect any serious or quick changes with his government entering office. The Commission itself is not directly affected by this change in any way, but the governmental attitude will surely change. Not necessarily in policy areas (the general attitude towards migration, abortion or gay rights do have some support from the Polish society). But in the case of a more constructive acceptance towards messages coming from the “Brussels bureaucracy” these messages will be less and less aggressive. Conclusion of various infringement proceedings, possible even of the Article 7 proceeding will surely lighten up the relationship. Brussels may cease to be public enemy no. 1 at least in governmental communications. We do not believe in direct interpersonal relationships being decisive in politics, but the general attitude of Tusk may determine the nature of the bilateral relationship in the future, leading to a better-balanced cooperation.

Questions may be asked about the member of the European Commission, Janusz Wojciechowski, delegated by the Polish government in 2019. Theoretically, a new Polish government could nominate a new commissioner, if the President of the Commission decides to change the commissioner. But this has never really been the European practice and even the idea has never been raised in relation with Mr. Wojciechowski, who has never been considered being a clearly political appointee, having his earlier career tailored to the European Union, too.

Some very similar things can be expected in relation to the European Parliament, which has developed a very critical attitude towards autocracy-leaning governments of EU member states in the past years. The clear difference is that the European Parliament has even less effect on member states’ politics and development of EU policies, but it has never stopped it from becoming a vocal actor related to those. Even in the case of a more pre-European Polish government, ongoing political debates about subjects with the Polish society with a more conservative agenda will still provide enough ammunition to various political actors keeping the relationship tense. But this kind of tension can be more of a positive tension – regardless of the sides. There may and probably will be debates about gay rights, abortion etc, but these debates may target the essentials of these subjects, and hopefully won’t go towards a full denial of the existence and relevance of the European Union. On the other hand, political actors within the European Parliament will use the change of government in Poland as an example against e.g. the government of Hungary, thus already existing tensions will not loosen up in Brussels or Strasbourg.

The change in the Polish government will have its direct effect on the Council and the European Council, of course. The decision-making bodies of the European Union, operating with the direct participation of member states’ governments will see some changes with the change of one of its most vocal and controversial members, which also brings a relatively high weight in the decision-making, thanks to its relatively high population number (currently carrying ca. 8,4% of the population). But at the same time we need to understand that this government will most probably be under a very serious political pressure at home, so we cannot expect a sudden change of policies in every matter (see the thoughts written related to the European Commission and policy areas). Additionally, the regional weight and influence of Poland cumulated under the previous government will be something that the new government will want to keep, and even if it will take some conflicts with earlier allies, like the Hungarian government of Viktor Orbán (especially with some interpersonal tensions between Mr. Tusk and Mr. Orbán), these will be taken with eyes on the Polish, not on the “European” good. Opposition towards Russia is one of those fields, but specifically there these states have already lost common ground a long time ago. Other than that, the new Polish government will probably be a tough opponent similarly to the previous one, but its opposition to certain questions will be harder to characterise as “anti-Europeanism” or plain “sovereignism” than the previous one’s.

At the end of the day, the European Union may find a less PiSsed, but much smarter Polish government. It will not be easier in any way.