Reflections on the illiberal revolution in the EU

Portugal displays pro-immigration sentiment in the wake of anti-immigration member-states

In my third year of university, I wrote a paper on political philosopher Edmund Burke’s “Reflections on the Revolution in France.” In this piece, he argued about the dangers of revolution, claiming that “tradition, customs, and manners that form our social institutions are invaluable because they are products of countless interacting minds, representing the past and the present, depositories of the wisdom of ages.” This essentially meant that he was against notions of liberalism because it sought to transform and destabilize conventional structures in society. By ‘conventional structures’, this can mean our network of relationships with our families, communities, religions, and social classes. Therefore, cultural heterogeneity poses a threat to the stabilization of these networks and can hamper collectivity in a democratic society.

Edmund Burke was absolutely right—today, much of the conflictions we see in society are a result of cultural intolerance to those who are much different than ourselves. And it is this exact fact that can explain much of the resistance against migration, whether it be in Europe or the US. However, what Burke’s theory fails to explain is the welcoming sentiment that some countries, such as Portugal, have for migrants that may not be culturally homogenous to them.

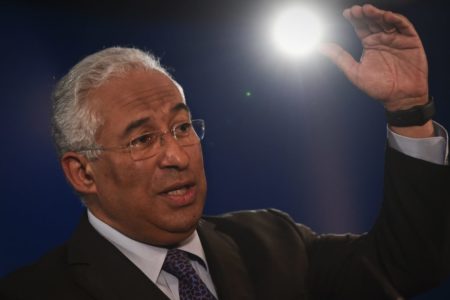

Portugal, contrary to a many other European countries, has expressed a desire for migrants to settle in the country and has displayed a number of actions that resemble this aspiration. When the Lifeline ship carrying migrants was stranded at sea after Italy had rejected it from its ports, Portugal was one of the first to open its doors to the migrants. As well, the government recently adopted a draft of a new regulatory measure that would make it easier for students to obtain visas or for people to create start-up companies. Portugal is also attempting to regularize the status of around 30,000 legal immigrants who do not yet have the authorization to work. In 2017, it issued 61,400 new residency permits, increasing the number of foreigners residing in the country by 6%. Additionally, from 2018-2019, Portugal will resettle 400 refugees residing in Egypt, through an agreement established between the EU and Egypt. If that did not convince you enough that Portugal is pro-immigration—Portugal’s Prime Minister Antonio Costa was just elected as the Director-General of the International Organization of Migration.

However, despite Costa’s open arms to migrants, only about 50% of the migrants who enter Portugal actually stay there, with the other 50% making secondary movements to other countries for reasons that can partially explain Portugal’s declining population. Following the recession after the 2011 financial crisis, around 300,000 Portuguese left the country for more economic opportunities—and incoming migrants are doing the same. Additionally, Portugal is experiencing a demographic problem with an aging population and declining birthrate which is leaving jobs left unfilled. According to a Strait Times article, the country needs a minimum of 75,000 new residents per year to maintain a stable working population. Therefore, much of Portugal’s desire for migrants can pinpoint to its need to boost its economic activity.

While it can be argued that Portugal has not necessarily resembled a tolerance for cultural heterogeneity in its society, but rather a need for workers to fill the gaps in its economy, there is still something to be learned from the country—the realization that migrants have value and can make contributions to improve the country, just like any other European citizen. A statement written by a group of European mayors stated that “[migrants] are not an abstract political issue—they are human beings with needs, responsibilities, and aspirations.” To fall short of realizing this is not only detrimental to the migrants’ ability to utilize their value, but also to European society, as it may ignore the benefits that stem from their diversity.

The only way we can achieve this, according to the mayors, is “if we manage to convince fellow citizens that migrants are not a threat” and “successful integration cannot be based on rejection and fear.” Referring back to Edmund Burke’s theory on cultural homogeneity and social cohesion, I had argued in my essay that attitudes toward heterogeneous groups may string from perceptions of threat, whether that be physical threat or a threat to one’s cultural identity, and can hamper cooperation. But I also argued that this intolerance is manageable because, despite largely yielding differences, democratic society submits to the legitimate authority of government. If a government attempts to orchestrate different cultural groups in a society, then society can be harmonized. However, if a government only represents one part of society and promotes the repression of another part, then the disputes continue.

Therefore, while a rising anti-immigrant sentiment in the public has caused a rise in populist parties, the influence can work vice-versa, with ruling parties having an impact on the sentiment displayed by the public. This was especially exemplified when US President Trump came into power and ignited intolerance towards immigrants from Mexico, declaring he would build a wall at the border. While Trump did not necessarily put these ideas and opinions into the citizens’ heads, he gave them the green light that this behavior was acceptable because “if our president can do it, then I can too.” Whereas, prior to Trump, America experienced its first African-American president and hostility was less prominent in the public. This can be a direct result of Obama’s efforts to create a tolerant, acceptant, and inclusive society.

In Portugal, Prime Minister Costa, not only showed a welcoming sentiment towards migrants, but also condemned anti-immigrant sentiment, stating that “we need more immigration and we won’t tolerate any xenophobic rhetoric.” Moreover, Costa has not only concerned himself with the responsibility of receiving migrants, but also the responsibility of ensuring fair and humane treatment in their journeys to Europe. Criticizing the EU’s new proposal for regional disembarkment platforms, the PM expressed that it is “absolutely unacceptable for the European Union to create ‘containment camps’ for refugees on the other side of the Mediterranean” and “creating containment camps on the other side of the Mediterranean, as if Europe wanted to free itself from its responsibilities.” Rather than appealing to the xenophobic voices in society in order to score cheap political points, Costa has sought to stand as a liberal role model for the Portuguese population, and direct them towards a tolerant and accepting society for the better of the country.

As the message by the group of mayors stated, “our attitudes determine whether migration will be a blessing or a curse,” and “we can only help newcomers embrace the values of equality, human rights, and democracy, which are the pillars of our societies, if we are able to demonstrate that we live by these values ourselves.” So, Edmund Burke, your claim that cultural homogeneity is necessary for collective agency is wrong—the guidance of leaders who can harmonize native and immigrant populations in society will also establish social and political cohesion. Additionally, your theory is outdated in today’s society where human progress occurs when we consider the ideas from a variety of minds. As philosopher William Kymlicka notes the importance of diversity, “it is only through having a rich and secure cultural structure, people can become aware, in a vivid way, of the options available to them, and intelligently examine their value.”