Roxana Nedelescu is a Senior Academic Assistant in the Economics Department at the College of Europe (Bruges). She holds a PhD in Economics and Finance of Public Administration from Catholic University of Sacred Heart in Milan, a MA in Management and Communication from the National School of Political and Administrative Studies in Bucharest and a BA in Economics of European Integration from Romanian-American University. She has also obtained certifications in business planning from James-Madison University and financial analysis from Barry University and Romanian-American University. Roxana has previous work experience in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Bucharest as well as Directorates General for Research and Innovation, Environment and Climate Change, within the European Commission.

Her research interests are EU Economic Governance and Decision-Making process, Financial Markets and Banking Union, Fiscal Federalism, Public Economics, Political Economy, Labour Market and Immigration, Economics of Climate Change and Applied Econometrics.

In the light of recent economic developments concerning Greek debt, the future of the Eurozone (EMU) seems even more at risk. While it is true that the European Union has been slowly putting in place the necessary institutions and mechanisms to address macroeconomic imbalances and to prevent further shocks, such as the ESM, SRM and SSM, the EMU has still a long way ahead from becoming sustainable on the long run.

First, and foremost, the Greek debt remains one of the problems that need to be addressed. At the end of June, the President of the European Council, Mr. Tusk, called for an emergency summit to discuss with EU leaders, the critical economic situation of Greece. By 30 June, Greece needs to repay 1, 6 bil. Euro to IMF, and in total approx. €9.7bn this year. Not meeting its international debt obligation, would induce Greece to default.

A Greek default would be a lose-lose game, with both political and social challenges to address and would without any doubt affect both Greece and the entire Eurozone system. Since other EU Member States own a high share of Greek debt (83%), they will lose in the process. Loss of wealth would occur in the country as Greece will not have the capacity to benefit from the depreciation of currency. Ultimately, it would lead to loss of trust in euro currency with financial markets lending at higher interest rates for other members, wondering who’s next.

In this setting, a very important question arises: implosion or future integration, what is the way forward for the EMU? But before answering this question, one needs to understand what are the alternatives[1] and furthermore what are their consequences.

Case 1. Implosion: Greece defaults and EMU disintegrates. EU would be divided in different blocks, with obvious division between Northern and Southern countries. This scenario would most probably lead to protectionist policies, bottlenecks in financial markets and credit crunch, deepening the economic recession and weakening the European Union overall. The Union itself may fall apart.

Case 2. Two or more speeds EMU, some Member States part of the Eurozone, some out: with the trouble-maker countries, outside the EMU, the countries that remain, could create a deeper single market, ensuring financial regulation and stability. However, former EMU countries would need financial assistance and struggle to go back to the economic growth path and re-join the Eurozone.

Case 3. Moving from crisis to crisis: Eurozone divergences will deepen, while unemployment will increase. The aggravate recession will lead to social outburst.

Case 4. Further integration: full fiscal and economic union. Requires strict fiscal rules and centralization of budgetary control, leading to an economic and fiscal union. Joint public debt could be issued, leading to a reduction of sovereigns borrowing costs. Ultimately, could lead to economic convergence, competitiveness and growth.

What happened so far? Several reform measures were proposed to the Greek officials during the EU Summit as a precondition to access the remaining bailout funds, so that international debt payment deadlines are met. The proposal enclosed 10 points (EC Press Release, 2015) concerning VAT (mainly, to be unified at 23%), other tax policies (such as increase corporate income tax from 26 to 28%, tighten tax evasion and fraud definition, etc.), tax collection as well as tax administration in order to ensure collecting fiscal contribution, pensions (among other measures, increase pension age and social welfare review having technical assistance from the World Bank), public administration (among others, wage grid reform and benefits as well as measures to enhance labour productivity), financial sector (several measures were proposed, ensuring insolvency legislation is in place), labour market (reform of collective bargaining legislation, to be proposed in cooperation with ILO and other international organisations and approved by the EC/ECB/IMF), product market (among others, reforms referred to electricity and gas markets) and privatization (reforms concerned mainly the transport sector). Some policies such as a reduced rate of 13% for basic food, electricity, hotels and water and a super-reduced rate of 6% for medicines were also mentioned in the package. These measures aimed to ensure a budgetary surplus for Greece, however not without placing more fiscal pressure once again on its citizens. As a response, Greek officials withdrawn from negotiations, placing the ball in Greek voters hands on the 5th of July referendum with a negative opinion, and asking them to decide whether they still want the euro or not. Meanwhile banks are closed and capital controls have been imposed.

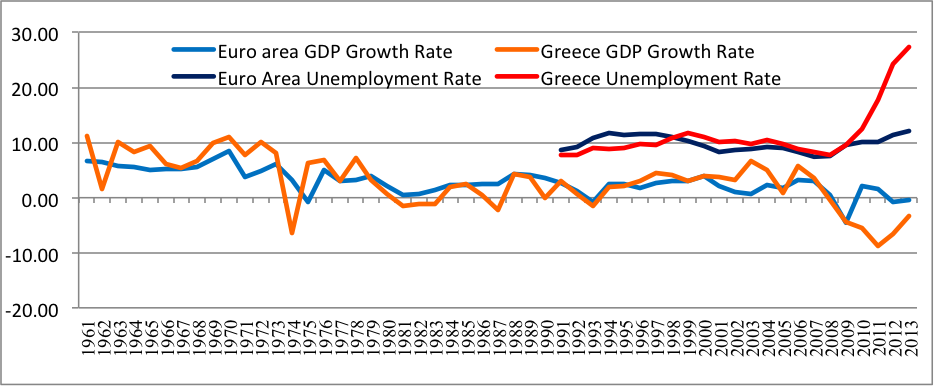

Where does Greece stand now? Based on available macroeconomic indicators as provided by the World Bank, in terms of economic growth since its EU accession, Greece was more or less in synchronization with other EMU countries, with some exceptions. However in Figure 1 below, an obvious decoupling as of 2009 can be noticed. It would be safe to say that Greece fare much worse during the economic and financial crisis than the other EMU members, partly because its high risk of defaulting and as such, borrowing with very high interest rates. On the other hand, in terms of unemployment rate there is an obvious difference as well as of 2009. In Greece, total unemployment was dramatically higher than the Eurozone average. What is even more dramatic is the youth unemployment rate in Greece, 1 youngster in 2 being out of work. Therefore it could be understandable from a social point of view, why Greek authorities were reticent in accepting the conditions imposed by the EC/ECB/IMF, even more so since previous austerity measures implied salaries and pensions cuts.

Figure 1. GDP Growth Rate and Unemployment Rate in EMU and Greece (%)

What to conclude? Is difficult to say what will come out of this Greek, or should I say, Eurozone tragedy. Without political coherence, it may as well be just a bargaining game, but quite a dangerous one. Certainly, further integration is desirable while a EMU implosion is catastrophic. An intermediary solution would be a middle-ground one, with the partial restructuring of the Greek debt, longer time-span for debt repayment and agreement to implement tailor-made reforms that may not only bring a balance surplus, but also would minimise the social cost for Greece’s citizens.

What is certain is that Greece needs to implement reforms that would ensure future economic growth. Problem is, that with decreased consumer confidence and reduced spending due to lower wages, on the short term economic growth would be difficult to be achieved. On the long run, investments and increased labour productivity might just do the trick. But in order for that to happen, the right legislation, market mechanisms, as well as political stability need to be in place.

All in all, it ain’t over till the fat lady sings.

[1] In Tsoukalis L., 2015, on M. J. Rodrigues, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 15 Perspectives on the Eurozone crisis, March 2013 and European Policy Centre, New Pact for Europe, 2014.