It’s right wing versus left, until the wings fall off our heads: the UK Election 2019

Source: Pixabay

Before the UK elections, the final YouGov model put the Conservatives on anywhere from 311 to 367 seats, with a prediction of 339. The magic majority is 326 of 650 seats.

In the cold light of day, the Conservatives hit the top end of that projection with 365 seats. What happened? How did it go so wrong for the Remain movement?

The election result cannot be wholly blamed on the electoral system, but this result will resurrect cries for reform. Under First Past The Post, if Candidate A gets 40% of the vote in Nowhereshire and Anytown, Candidate B gets 20%, Candidate C gets 20%, Candidate D gets 15% and Candidate E gets 5%, Candidate A is elected.

Unfortunately for the people of Nowhereshire and Anytown, they are now represented by an MP that 60% of voters didn’t want. This system leads to disproportionate success for parties that can count on concentrated support in particular areas and makes it harder for new and small parties to gain (and keep) a foothold.

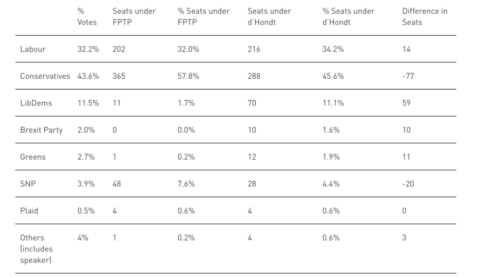

The Electoral Reform Society modelled the 2019 election results with the kind of Proportional Representation also used in the UK European Parliament elections. The results were as follows:

Although the Brexit process will now drive forward, it is debatable as to whether that reflects the true will of the people. A proportional result would have led to a hung parliament and some difficult and possibly different decisions.

However, the UK is where it is. The Labour Party faces a massive hill to climb if it is to have any chance of returning to government. A centre-left British think tank, the Fabian Society, has analysed the scale of the challenge. The party needs to win at least 123 seats at the next General Election to have a majority of 1. That will involve regaining marginal seats, the seats lost in its heartland, and formerly safe Conservative seats where demographic change could give it a fighting chance. It will also need to take SNP held seats or work with them. An SNP-Labour government would require Labour to win 83 seats from other parties, which, again, would be a tall order.

They note that one of the reasons for the Conservative majority was the split progressive vote. In 56 Conservative seats, the Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green vote combined was higher than the winning Conservative vote. The tragedy of FPTP, however, is not the whole story. Datapraxis, a polling and analysis company, has produced an initial report of the factors underlying the Conservative victory. It makes tough reading for British progressives.

In short, the Conservative victory was a result of ongoing Labour decline in its heartlands, combined with sceptical attitudes to a UK political system seen as rigged and out-of-touch, anti-immigration feelings, and a perception that social security and public services are being exploited by others. The UK has an ongoing tradition of sensationalist and misleading news, which has escalated with the rise of social media. Brexit provided a ‘way out’ to an imaginary renewed UK.

Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership is the elephant in the room. He is fundamentally unpopular among the kind of voters Labour needed to retain. Datapraxis calls this the most significant factor in Labour’s decline. 52% of Labour Leave voters disliked him, and 48% of them disliked Johnson. They were potentially winnable – 54% of them listed the NHS in their top two issues – but they were turned off by Corbyn’s radical left-wing views, Labour anti-Semitism issues, and saw him as unpatriotic. Conservative Remainers saw him as a danger to the country that they were forced to avert by reluctantly continuing to vote Conservative despite their dislike of Johnson. 1.3 million Labour Remainers went to other Remain parties: in some seats, they could have made the difference by staying with Labour. Its late conversion to supporting a confirmatory referendum on Brexit stopped it from haemorrhaging voters to the Liberal Democrats, but the damage was done.

A short note on tactical voting: progressive parties have debated whether closer cooperation could have avoided this. The Liberal Democrats campaigned against both Labour and the Conservatives, and bad blood remains between Labour and the Lib Dems over the latter’s coalition government record. Labour supporters particularly resent Lib Dem defector Sam Gyimah for standing in Kensington, which narrowly fell to the Tories.

According to Datapraxis, the Liberal Democrats’ message about Jo Swinson potentially becoming Prime Minister was one of the worst-performing messages the company had tested in Europe. The message that Britain deserved better than Corbyn or Johnson was much better received. The party was unable to mobilise a strong, substantial campaign to match it and did not connect with the soft Conservative vote it needed to win over. Even if the two parties had made a full electoral pact, Datapraxis modelling suggests 78% of non-frontrunner progressive voters would have had to vote tactically – an eye-wateringly high success rate. Even if this were possible, under the model, the Conservatives would have remained the largest party in a hung parliament.

Finally, a summary of the Scottish question. The Scottish National Party (SNP) won 45% of the vote, and 80% of the seats, in Scotland. Many of its politicians have raised the question of a mandate for another Scottish independence referendum. However, as a result of the voting system, this mandate is also questionable. 45% is also the share of voters who backed independence in 2014. Only 10 SNP candidates got over 50% of the vote: it is mathematically possible for the other 38 to win by mobilising existing pro-independence voters. In any case, Johnson has clearly stated his opposition to a second vote, and the Scottish Government has made it equally clear that it will not repeat the Catalans’ mistakes. Sturgeon has stated she will not hold a referendum without the consent of the UK government. The only certainty is that there will be political and potentially legal disputes. Even with consent, a referendum could not practicably be held before the 31st January 2020, and Scotland will leave the EU with the UK. Anything beyond that remains unpredictable.

A silver lining for UK progressives? Boris Johnson’s government has nobody left to blame but itself. Having won over traditionally Labour-supporting areas, they now have a voter coalition that includes formerly industrial Blyth Valley and affluent ex-Liberal Democrat seat Cheltenham. This is a naturally fragile group and may collapse under the weight of EU-UK negotiations on the future relationship. Corbyn may have been hated, but Johnson is hardly loved. Datapraxis found that he was described, time and again, across all age groups, political loyalties, and genders as ‘the best of a bad bunch’. If Labour can find someone seen as better than Boris, and the Liberal Democrats can build on their second-place results in the South, there is potential for a long, slow recovery.